Engineering and the human body

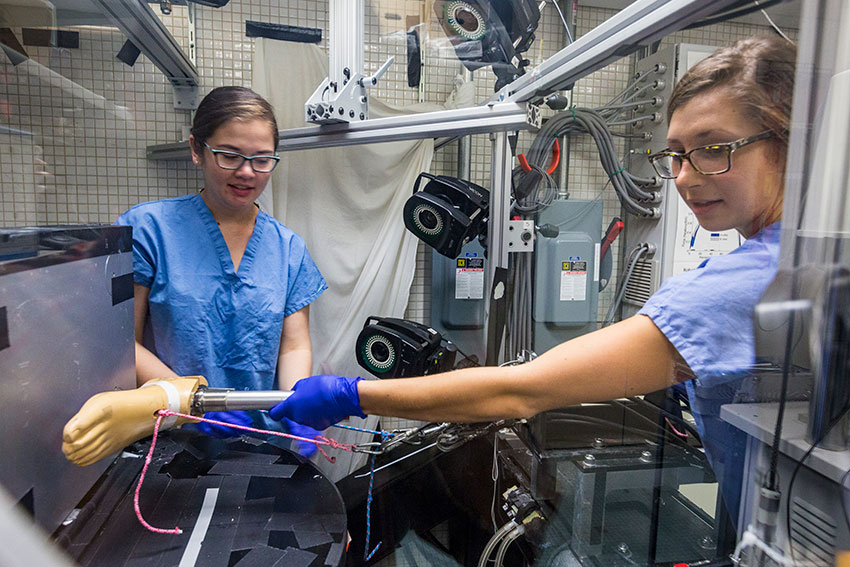

Campus labs provide students with opportunities to explore a range of biomechanics applications. In the AMP Lab, for example, researchers investigate the dynamics and control of movement to design treatment strategies and assistive technologies that improve function and quality of life. Mark Stone / University of Washington

According to Hector Iturribarria Bazaldua, the most exciting aspect of biomechanics is the “unknowingness.”

“In biomechanics we look at the human body as a complex system, a machine. But every human body is different and they’re always changing,” he explains. “This unknowingness makes biomechanics a challenging but fascinating area to study.”

Bazaldua, who received his ME bachelor’s degree last spring, was part of the department’s first cohort of students to graduate with a concentration in biomechanics. Along with mechatronics and nanoscience and molecular engineering, it’s one of three degree options in which ME undergrads may choose to focus while at the UW.

“Using mechanical engineering approaches to understand biological systems — and vice versa — has long been a strong interest area for ME researchers,” says ME associate professor Kat Steele, who coordinates the biomechanics option with ME professor Nate Sniadecki. “Our goal is to formalize an academic framework for it and legitimize it as a professional pathway for students.”

ME’s ongoing partnership with the Seattle VA’s Center for Limb Loss and MoBility provides hands-on research opportunities for students and has helped propel biomechanics research in new directions. Mark Stone / University of Washington

“ME has a rich history of advancements in biomechanics and health technologies, thanks to the work of pioneers such as emeritus faculty Albert Kobayashi and Colin Daly and alumni Wayne Quinton and Savio Woo,” Sniadecki adds. “Plus, the department has partnered for nearly 20 years with the Seattle VA’s Center for Limb Loss and MoBility, a collaboration that has helped propel biomechanics research in new directions.”

Even as a sub-field of mechanical engineering, biomechanics is quite diverse. Researchers work in areas ranging from ergonomics, human factors design, cell mechanics, cardiovascular fluid dynamics and human-machine interaction to the development of medical devices, electronic wearables and sports equipment.

Last spring 10 students completed the program. Moving forward, Steele and Sniadecki hope to see 20-30 ME students graduating from it each year.

Pursuing biomechanics

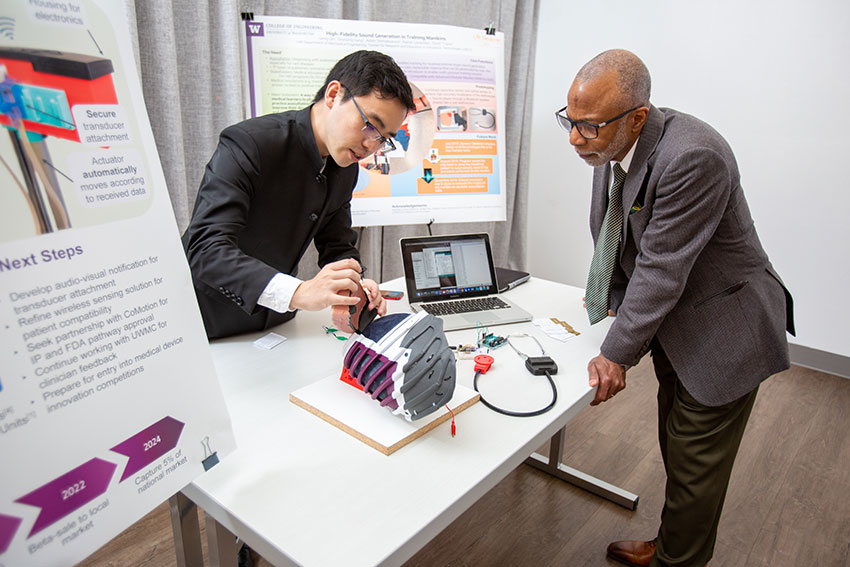

Biomechanics researchers work in a range of areas, including human factors design and human-machine interaction. Mark Stone / University of Washington

To graduate with a biomechanics concentration, ME undergraduates must complete 19 biomechanics credits. ME 411, Biomechanics Frameworks for Engineers, and ME 419, the Biomechanics Seminar, are required. Beyond those, students select electives tailored to their interests.

“ME 411 was so engaging,” remembers Toni Erwin, who graduated from ME last spring. “We learned how to apply fundamental principles of engineering to systems within our own bodies and analyzed the science behind those systems to make predictions about human bodies more broadly.”

Erwin says that the electives opened up new ways for her to explore engineering. She took courses she would have otherwise shied away from, such as classes in vibrations and finite element analysis.

“These classes focused on system dynamics, which had never been interesting to me until I started applying it in a biomechanical sense,” she says. “For example, in my vibrations class I tackled engineering challenges related to oscillation of movement in structures and systems — something very important in analyzing motion capture data or designing a prosthetic device to reduce impact on the residual limb.”

ME’s biomechanics does not require a pathway specific capstone project. However, many students choose to participate in Engineering Innovation in Health (EIH) — the department’s capstone program that connects local clinicians with student teams to solve pressing healthcare challenges — as program credits count toward the option. So, too, do credits from internships at places such as the Seattle VA.

Biomechanics students often take part in Engineering Innovation in Health, ME’s year-long program that partners engineering students with clinicians to design medical devices aimed toward lowering costs and improving care. Matt Hagen / Engineering Innovation in Health

ME graduate Ian Johnson did both. “During my sophomore year I interned at the VA where I helped create 3D-printed foot models for researchers working to enhance mobility in people with foot and leg impairments,” he says.

Then during his senior year, he took part in EIH and was on a team called DopCuff, which created a device to get more accurate blood pressure readings.

“Having real-world experience like these projects and working alongside clinicians, professional engineers and sometimes even patients was so valuable,” he says.

Becoming a more well-rounded engineer

During the winter quarter seminar, biomechanics students have the opportunity to hear from industry leaders and professionals, connecting them to potential post-graduation career opportunities. Since it’s only offered once each year and can help students decide if the biomechanics option aligns with their interests, Sniadecki advises students interested in the biomechanics concentration to take the seminar before their senior year.

Irwin, Johnson and Bazaldua say that their biomechanics background played a key role in the jobs they now have, even if those jobs are not directly related to the field.

“The skills I gained through biomechanics helped me become a more well-rounded engineer, something companies really value” says Erwin. Now a mechanical design engineer at Katerra, she hopes to attend graduate school in the future so she can further her studies in biomechanics.

Johnson is a mechanical engineer at Pure Watercraft, a company that makes electric motors for boats. Though his current position is not directly involved in biomechanics, he says there’s opportunity to move in that direction once he has more on-the-job experience.

And Bazaldua, who now works at The Boeing Company on flight deck design and crew operations, finds that he draws from his background every day.

“My team’s work is concentrated in human-machine interaction, especially how pilots and crew interact with airplanes,” he says. “It’s very biomechanics, which makes my job complex but cool to work on.”

[Source : https://www.me.washington.edu/news/2020/01/08/engineering-and-human-body]